A Commentary on Warfare and Politics

Volodymyr Yahnishchak

An Unknown Diary about the Zhuravno Battle near Zhuravno (September 25th – October 14th, 1676) and the Treaty of Zhuravno (October 17th, 1676)

In general the internal politics of the European powers were proving disastrous for the making of a broad Anti-Ottomans Alliance in the 1670s [406]. Despite the successes of the King Jan III Sobieski aganist the Ottomans in the 1673-1676 war, once again he was faced with little support from the own country; the nobles jealous of his success, refused to sponsor a larger army and the Commonwealth diet did not give him any support too. To overcome this weaken support from his own country’s nobility, the King Jan III Sobieski sought an alliance with France. His wife was a member of the Bourbon royal family of France named Maria Kazimiera d’Arquien de la Grange. Because of her, King Jan III Sobieski’s alliance with France was secured until the Treaty of Zhuravno in the October 17, 1676.

In the secret alliance, the King Jan III Sobieski was to attack Brandenburg then a Hapsburg (Austrian) domain and in return France was going to attack the Ottoman Empire and retrieve Podillia for the Commonwealth. The nobility of the Commonwealth, however, were not interested in fighting against Brandenburg in alliance with France; so they concentrated their troops on attacking the Ottoman Empire, instead. With the French alliance in doubt, the King Jan III Sobieski, eventually had to look out for other allies to protect his country’s interests and the larger interests of Christendom. So he entered before the Treaty of Zhuravno in the October 17, 1676 to an Anti-Ottomans Alliance with the Hapsburgs of Austria, France’s long-standing enemy during the 17th century.

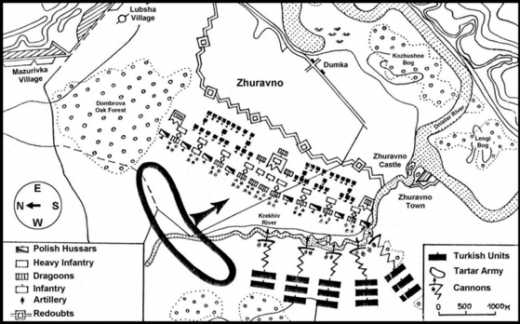

These internal politics of the European powers were proving disastrous for the making of a broad Anti-Ottomans Alliance. Taking advantage of this confusion, the Ottoman Empire attacked Austria in 1675. The Commonwealth, under their Anti-Ottomans Alliance, gave troops to help Austria (ruled by the Hapsburgs). But with this move, they had to formally break the alliance with France. Unfortunately Austria proved to be a weak ally, not pulling their weight in battles with the Ottoman Empire and even conniving against the Commonwealth to limit their power to conclude a separate peace with the Ottomans. The Ottoman Sultan used these divisions in the European powers to the hilt and made further inroads into both the Commonwealth and Austria. In the summer, 1676 the Ottomans invaded the Commonwealth again with over 200, 000 men, most of them were Tatars. With only 8, 000 soldiers the Poles, Lithuanians and Ukrainian Cossacks held them at their camp near Zhuravno for nearly three weeks, until October 14, 1676.

The Ottomans finally called for peace after the battles near the villages of Voinyliv and Dovha and the town of Zurawno which was signed in October 17th, 1676. While the Ottomans kept most of the territory they had gained, including the province of Podillia, but they pledged to end further attacks and released most of the prisoners (15, 000 after the Battle at Zhuravno) they had taken. After the Treaty of Zhuravno having waged costly campaigns against the Commonwealth and having had to pay very heavily in terms of casualties, the Ottomans turned on the more lucrative of their Christian foes, the Hapsburgs of Austria. By the end of the 1676, after ceaseless war with the Ottomans for over three decades, the Commonwealth had been reduced to half its size. But for these victories, the Ottomans paid heavily in terms of lives lost of hundreds of thousands of its warriors (near Zhuravno the Ottomans lost more than 20, 000 men, and in the Battle at Voinyliv and Dovha almost 3, 000 men in September 23, 1676) and this strain was making further incursions into the Commonwealth and Muscovy state unattractive.

The Battle of Zhuravno (there were actually several battles from September 25th – October 14th 1676) and the Treaty of Zhuravno, October 17th, 1676, (Turkish name: Treaty of Izvanca between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, ended the second phase of the Polish-Ottoman War (1673-1676). It revised the 1672 Treaty of Buchach, and was more favorable to the Commonwealth, which no longer was forced to contribute taxes, and regained about one third of the territories in the Right Bank Ukraine lost in the Buchach Treaty(1672).

The Treaty of Zhuravno has eight paragraphs. The all territory of the Right-Bank Ukraine except two fortress Bila Cerkva and Pavoloch became under the Ottoman’s vassal power – the Right-Bank Ukraine, Hetmanate. After the eighteen months of negotiations in the April 7, 1678 the Ottomans Sultan signed the Constantinople Treaty, what was a ratification of the Zhuravno Treaty. The number sixth paragraph was no longer in favor to the Right-Bank Ukraine Hetmanate, now (1678) it was written in the official document that the Right-Bank Ukraine is under the Ottoman vassal power. This Treaty also drew a demarcation border line between the Commonwealth and the Ottomans.

It also stipulated that the Lipka Tatars were to be given a free individual choice of whether they wanted to serve the Ottoman Empire or the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. In addition, it reaffirmed the cession of the province of Podillia to the Ottomans. The Right-Bank Ukraine, with the exception of the Bila Cerkva’ and Pavoloch’ districts, was placed under the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian Hetman, a vassal of the Ottomans at that time.

The Treaty of Zhuravno can be seen as part of the Great Turkish War and as part of the series of wars between the Ottomans and Europe in the second half of the 17th century [407].

During the time of two wars against the Commonwealth (1667-1672, 1673-1676) and the war against Muscovy and Left-Bank Ukraine Hetmanate (1676-1681) the Ottomans Sultan Mehmed IV became the protector over the Right-Bank Ukraine. The Ottomans policy was based on keeping the Right-Bank Ukraine in the Ottomans protection and buffer against the Commonwealth and Muscovy. First of all the Ottomans formally keep the Right-Bank Ukraine Hetmanate like the Ukrainian Cossack state, however this state was a vassal of the Sultan. Second in the province of Podillia the Ottomans ruled like in any their provinces after the 1672 (the Treaty of Buchach) until the 1699 (Karlowitz Congress). The Right-Bank Ukraine in the provinces of Kiev and Braclav the Ottomans officially call this state "Ukraine" with a very limited autonomy.

In September 9, 1676 hetman Petro Doroshenko switched to Muscovy protectorate and changed all Eastern Europe balance of policy. However the Ottomans did not want to give up in the "Ukraine" and rely on the Treaty of Zhuravno as the main international document between the Ottomans and the Commonwealth for the Ottomans present in the "Ukraine". Thus in the summer 1676 the Sultan relieved from the prison hetman Yurii Khmel’nytsky and after the September 9, 1676 proclaimed him as the hetman of the Ukraine and started to prepare the war against Muscovy and the Left-Bank Ukraine.

The Ottomans policy at that time was to "weak" the Commonwealth and Muscovy and prevents any agreement between them against the Ottomans. That is why the Ottomans stabilized political situation in the Right-Bank Ukraine just to have the better strategic place in the Central, Eastern and South-East Europe. That is why the Ottomans helped the Duchy of Ruthenia (official title of Ukraine) of Yurii Khmel’nytsky in the 1677-1685, the hetmans G.Duca, T.Sulymko and in 1681-1685 in the provinces of Kiev and Braclav in the Right-Bank Ukraine and the Ottomans also provided direct administration in the province of Podillia (1672 – 1699).

The Ukrainian historiography does not give a full account of the Treaty of Zhuravno and its influence on the development of international relationships in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe in the later part of the 17th century. The Treaty of Zhuravno can be seen (from the Ukrainian historiography’s point of view) as final stage of the Ukrainian Revolution, started in 1648 by Hetman Bohdan Khmel’nytsky, who proclaimed the Ukraine an independent state (’Viysko Zaporozhske ’), as much as it was possible, and finished by Hetman Petro Doroshenko in the 1676, who tried to survive as the Ottoman’s vassal (since 1669) but was finally self exiled to the state of Muscovy.

The Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) divided, for the third time in the second half of the 17th century, the Cossack’s Hetmanate between the stronger states: Muscovy, the Ottomans, and the Commonwealth. The Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) and the Treaty of Buchach (1672), on the other hand, did not establish permanent power of any monarch because of the balancing or poly-vassal policy of the Hetman Petro Doroshenko. Thus, the Treaty of Zhuravno brought permanent changes to the division of the Right-Bank Ukraine.

According to the Treaty of Zhuravno until the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) the Ottomans had the internationally recognizable right to posses the south part of Kiev province and the province of Podillia. The Treaty of Zhuravno caused political and economic ruin to these provinces even into the 18th century. The Treaty of Zhuravno recognized the loss of the Right-Bank Ukraine’s (Hetmanate ) status as the state . The Ukrainian Hetmanate in the Right-Bank of Ukraine was no longer subject to international law at that time.

The Treaty ended four years of the Polish-Turk war (1672-1676), but it did not resolve the conflict around the Right-Bank Ukraine. After October 17th 1676, Muscovy blamed the Commonwealth for betrayal of the Andrusovo Treaty (1667) and believed that the Right-Bank Ukraine (Hetmanate) must belong to Muscovy, which opened the door to the war between the Ottomans and Muscovy together with the Left-Bank Ukraine (Hetmanate). The Muscovy Tsar and the Hetman of the Left-Bank Ukraine (Ivan Samoilovych) in fact occupied the Right-Bank Ukraine and did not agree with the Treaty of Zhuravno. The Treaty of Zhuravno sparked the Russo-Turkish War (1676-1681) as well. The presence of the Tsar’s army in the fortresses of the Right-Bank Ukraine started the Russo-Turkish wars of 1676 and 1678 in the territory of the Right Bank Ukraine what was the first stage of the Russo-Turkish war 1676-1681.

In April 7, 1678, the Ottomans finally "granted" the Treaty of Constantinople to the Commonwealth; this was the formal ratification of the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676). However, paragraph sixth, which had a significant impact on the Right-Bank Ukraine was different, as it was in the Treaty of Zhuravno on October 17th, 1676. It stated that the Right-Bank of the Ukraine now must belong to the Ukrainian Cossacks, who were the vassal of the Ottomans at that time. However, the King Jan III Sobieski understood that it was the Ukrainian Cossacks who were ruled by the Ukrainian Hetman E. Hohol, who was a vassal of the Commonwealth, and following this logic all of the Right-Bank Ukraine must belong to the Commonwealth because the Ottomans gave this territory to the Ukrainian Cossacks in the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) and in the Treaty of Constantinople (1678), which was in fact ratification of the Treaty of Zhuravno. The Commonwealth will still have two fortresses Bila Cerkva and Pavoloch in its possession. In 1681, the two empires would demarcate their borders in 1681 [408].

The Commonwealth wanted to protect its state from the Ottomans after the Treaty of Zhuravno that is why the Commonwealth signed an agreement with Muscovy in 1678 and the "Eternal Peace" on May 6th, 1686. In 1681, Muscovy signed an agreement with the Ottomans in Bakhchysaray (the capital city of the Crimea Khanate) and according to this agreement the Right-Bank Ukraine must belong to the Ottomans and the Crimea Khanate. They finalized this treaty in April, 1682. Neither state looked upon this agreement seriously: they knew the treaty was temporary because it did not solve the problems of the Cossack Ukraine.

The Zhuravno Treaty can be seen why the Ukrainian Hetmanate in the Right Bank Ukraine (or the "Duchy of Ruthenia") became one of the biggest political issues in Eastern Europe, in the unstable situation between the Islamic East and the Catholic West. The Ukrainian Hetmanate greatly influenced all world politics in the second half of the 17th century and changed the European political map in the second half of the 17th century because of the Treaty of Zhuravno what created an imbalance between the Commonwealth, the Ottomans, and Muscovy.

This Zhuravno Treaty can also be seen as an important part of the Commonwealth war against the Ottomans, and right after the signing of this treaty the Ottomans started to fight against Muscovy state. This treaty nullified the alliance with France and started a new alliance with Austria. This treaty also can be seen as the culmination point, after which the Ottomans started long term war against Muscovy in the 17th century and later a long term war against the Russian Empire in the 18th and 19th centuries.

It is important to understand that the Ukrainian Cossacks would accept Muscovy protectorate, but not really the Ottoman’s vassal status like they obtained it in the Treaty of Zhuravno. The Ukrainian Cossacks would accept Muscovy rule, but not Ottoman domination. That was a period of the consolidation of the Eastern Orthodoxy in the Russian Orthodox Church (Patriarch Nikon’s Russian Church reform 1666-7) as a reaction to the expansion of the Commonwealth’s Roman Catholic Church in the Ukraine, and expansion of the Ottomans’, and Tatars’ Crimea Khanate, Islam. Muscovy Tsar Aleksey (1645-1676) and Patriarch Nikon (from 1652) made the religious practice in the Muscovy Russian Orthodox Church more like that of the Greek and Ukrainian Orthodox Churches. These changes were formalized in the Russian Orthodox Church Council of 1666-7 [409].

This period also was inspired by Russian Orthodox Church reforms and provided political balance between the Ottomans, the Crimea Khanate, the Commonwealth and the Ukrainian Cossack state.

The second half of the 17th Century was a period of time in Eastern Europe when the Ukrainian Cossacks crushed the Commonwealth in 1648 – 51 and brought Muscovy into the war as the Ukrainian ally. At the same time (second half of the 17th century), the Ottomans having been in a permanent war with Christendom, became the bigger ally with Catholic France and protestant Sweden and took the "Ukraine" under their power when the Hetman Petro Doroshenko lost independence and became a vassal to the Ottomans. The main figures in the East Europe became the Cossack leaders in the 1670s who did not want to lose independence from any states: the Commonwealth, who occupied all of the Right-Bank Ukraine, and Muscovy in the Left Bank Ukraine which was formally under Muscovy protectorate since 1654 (The Treaty of Pereyaslav ) and the Ottomans who occupied the province of Podillia and the Right-Bank Hetmanate after the Treaty of Buchach in the 1672 until the Congress of Carlowitz in the 1699.

Hetman Petro Doroshenko tried to get support from Constantinople, offering to accept the sultan’s domination in return for the Ottoman’s protection and military assistance. In addition, the war between the Commonwealth and Muscovy over the Right and Left Banks of the Ukraine in the 1670’s showed great possibility for the Ottomans to protect themselves from the Zaporozhian Cossacks in the area of the Black Sea. The Ukrainian state and the Black Sea had strategic importance for the Ottomans, the Commonwealth, the Crimea Khanate, and Muscovy (since 1654) in the 17th Century; however, it was only the Ukrainian Cossack state, which could protect any state with the alliances with any other states [410].

That is why the Ottomans, in 1668/9, made the decision to take the Ukrainian Cossacks on the Right-Bank of the Ukraine, under their protection, directing their attacks in any directions except South. Consequently, the province of Podillia and the strategic fortress of Kamyanec’ Podil’sky on the Dnister River became a keystone to the Ottoman’s rule over the Right-Bank Ukraine, Moldavia and the Crimea Khanate. Also, two main Tatar attack routes into the Commonwealth (the Volosky and Kuchmansky trails) ran across the province of Podillia. The foreign policy of Sultan Mehmed IV, who was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687, changed the nature of his position for ever by giving up most of his executive power to his Prime Minister (Grand Vizier) and he never took part in any military campaign personally, because his policy was based on a position that the Ottomans neighbor must be permanently weak [411].

In June 1669, the Ukrainian, Hetman Petro Doroshenko, was accepted as a vassal by the Ottomans [412]. In the Crown (Poland), the Grand Hetman Jan Sobieski invaded the Cossack’s Ukraine. At the same time, August 18th, 1672, the Ottomans took over the strategic fortress of Kamyanec’Podil’sky. In accordance to the Treaty of Buchach (October 23, 1672), the province of Podillia was ceded to the Ottoman’s protection. The Lipka Tatars, who had settled in Lithuania in the fifteenth century, and recently rebelled against the Commonwealth, were to be allowed to emigrate to the Ottoman’s lands with their families and belongings. The Commonwealth started to pay a yearly tax to the sultan and this meant that the Polish King Michal Wisniowiecki (1669 – 1673) legally became the Ottoman’s vassal. The Commonwealth diet rejected the Treaty of Buchach and voted in new taxes for military protection. The army was increased to over fifty thousand men and, in November 1673, Jan Sobieski (Crown Hetman) defeated the Ottoman army at Hotyn (fortress in the province of Podillia), which brought him the Polish crown after the death of the Polish King Michal Korybut Wisniowiecki, (July 31, 1640 – November 10, 1673).

Finally, on September 25 th, 1676 the new Ottoman commander, Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha, besieged the royal (Jan III Sobieski) army enclosed in the fortified camp at Zhuravno, province of Galicia. Before the siege at Zhuravno in September 16th, 1676, the Polish King sent six Polish commissioners to the Ottoman camp [413]. Initially the Commonwealth wanted to regain as much of the province of Podillia and the Ukrainian Cossack state territory as possible, while the Ottomans hoped for a future common action against Muscovy presence in the Ukraine (on the Left-Bank of the Dnieper river) [414].

The final conditions, negotiated on October 14th -17th , 1676 confirmed the Treaty of Buchach (1672) with only two notable exceptions: the taxes were abolished and two the Right Bank Ukraine fortresses, Bila Cerkva and Pavoloch were left to the Commonwealth. The temessuks [415] were exchanged on the 17th of October, 1676 in Zhuravno. The temessuk was a simple receipt of confirmation, the agreement reached between the Ottomans Pasha and the Commonwealth Commissars on behalf of their masters, in order to maintain peace was to be maintained in the land between the Ottomans and the Commonwealth. The Treaty of Zhuravno had to be confirmed in a formal ’ahdname [416] granted by the Ottoman’s Sultan. The text of the new ’ahdname received in April 1678 by the Commonwealth ambassador indicated that it was issued on the basis of the Zhuravno’s (October, 17, 1676) temessuks.

While in the European literature the Treaty of 1676 is known as the Treaty of Zhuravno, from the Ottoman legal point of view, the ultimate conclusion of the peace occurred by the granting of the imperial ’ahdname. An ’ahdname was issued in eighteen months (1676-78) after the temessuk on October 17th, 1676 at Zhuravno. Immediately after signing the truce, Andrzej Modrzejewski (October 17th, 1676 at Zhuravno) was appointed a "small envoy" and accompanied the Ottoman army to Constantinople, charged with the task of dealing with the Ottoman authorities until the arrival of the great Polish embassy of Jan Gninski in 1677 [417]. Even though Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha led the Polish commissioners to believe that their ambassador in Constantinople would obtain much better peace conditions than those agreed at Zhuravno. The oral promises given by Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha at Zhuravno lost their weight because Pasha fell in disgrace after the Ottomans military campaign in the Right Bank Ukraine in 1677. The new treaty, granted finally in April 7th, 1678, was in fact a confirmation of the Treaty of Buchach (1672), with the exclusion of the taxes and the concession of Bila Cerkva and Pavoloch (two the Right-Bank Ukrainian fortresses) which were left in the Commonwealth’s hands.

The inhabitants of Kamyanec’Podil’sky and other Podillian localities were allowed to return to their homes. Nobles were allowed to collect their own taxes and to pay them in a lump sum. The Catholic community in Podillia enjoyed freedom of worship, and at least one Catholic Church in every sandjak (Turk’s administrative-territorial center) was to be restored. The border of Ottoman’s Podillia was to be defined by the commissioners of both sides.

Moreover, the Lipka Tatars, who were fluent in Polish and Ruthenian (Ukrainian), knew the country and were notorious for their raids into their former homeland after the emigration to the Ottoman domains. They were not allowed to settle in Podillia [418].

The Ottomans provided for free trade in the Mediterranean and by the ships of the royal city of Gdansk (in the Commonwealth) and their protection from the Muslim corsairs (pirates) of the Barbary Coast.

In regards to the conflict over the Holy Sepulchre, which had been granted to the Greek Orthodox Church (in the Ottoman Empire) in the first half of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman Porte confirmed the traditional rights of the Franciscan monks in Jerusalem, but the Polish and Ottoman interpretation of this article differed substantially. Contrary to Polish expectations, the Holy Sepulchre was never restored to the Roman Catholic Church. This paragraph in the Treaty of Zhuravno also developed one of the main reasons of the Crimean war (1853-1856) between the Russian Empire and the alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Duchy of Nassau. The Crimean war developed because of an argument between the French (Catholic) and Russian (Orthodox) religious fraternities over who should have access and right to holy areas in the Middle East (Nazareth and Jerusalem).The both sides of the conflict based their position on the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) [419].

By the time Jan Gninski (the Commonwealth envoy to the Ottomans in 1676-78) returned from Constantinople in 1678 with the ratification of the Treaty of Zhuravno, it was too late for the Commonwealth to attack Prussia because France aligned itself to Prussia. In the same year, the Treaty of Nijmegen was signed and Louis XIV was no longer interested in an alliance with Warsaw [420].

The year 1676 marked the end of the political career of Hetman Petro Doroshenko who wanted the Ottomans to help him expel the Muscovy garrison from Kiev and restore his rule over the Left-Bank Ukraine, held by the pro-Moscovy, the Left-Bank Ukraine Hetman Ivan Samoylovych. However the Ottomans were not really ready to go to war with Muscovy; therefore, they strengthened their control over the province of Podillia and tried to garrison their troops in the Right-Bank Ukrainian towns. In 1674, the Ottomans had to help Hetman Petro Doroshenko quash his own rioting subjects, who were assisted by Muscovians. In the end, the disillusioned Hetman tendered the insignia he had obtained from the Sultan to Moscovy and was granted exile by the Russian Tsar Feodor III in September 9, 1676. One of the most gifted Ukrainian leaders of the seventeenth century, Hetman Petro Doroshenko, left the Ukrainian state which was falling further into the "Ruin" period [421].

The effort to regain control over the Right-Bank Ukraine and to install Hetman (Prince) Yuriy Khmel’nytskyy (instead of Hetman Petro Doroshenko) as the hetman led the Ottomans to war with Muscovy. After an unsuccessful campaign in 1677, the next year the Ottomans expelled the Muscovian garrison from Chrhyryn (fortress), the traditional seat of the Ukrainian hetmans. The war was ended by the Truce of Bahchesaray, concluded in January 1681, and officially granted by Mehmed IV in April 1682. The Treaty divided Ukraine along the Dnieper River, with Kiev left in Muscovian hands [422].

The Ottomans granted their part of the Right-Bank Ukraine to the Moldavian Hospodar George Duca, who during two successive years of peace, was quite successful in restoring the economy of the province [423].

The Treaty of Zhuravno (’ahdname of 1678) also created the Polish-Ottoman demarcation of 1681 [424].

The Ottomans were engaged in the second Chyhyryn campaign of 1678 and needed the Commonwealth to evacuate their garrisons in the fortresses: Bar, Medzhybizh, Kalnyk and Nemyriv in September 1678. However, the new Treaty was ratified by the diet only in 1679, that is why the Ottomans only started demarcation in July of 1680. From the Polish side, a leading role was played by two men: Colonel Jerzy Wielhorski, and the standard-bearer of Sanok, Colonel Tomasz Karczewski. They were the same men who had affixed their signatures to the Commonwealth on the Truce of Zhuravno on October 17th, 1676 [425].

The Russian historiography established the position that the Ukrainian Cossack’s state after the Thirty Years War (1618-48) became the keystone to the organization of the "block" with Sweden, the Ottomans and the Commonwealth against Muscovy and to stop Muscovy from marching to the Baltic and Black Seas.

The Treaty of Zhuravno was signed by the Polish King Jan III Sobieski, because the Commonwealth did not have enough troops to extend the war against the Ottomans in 1676 [426].

A small group of Poles (Prince Lubomirski) defeated the Tatars near the village of Voynyliv and the village of Dovha in September 23, 1676 (4 miles toward the South-East of Zhuravno) man slaughtering 4, 000 Tatar men. This event caused the Ottoman commander (Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha) to attack King Jan III Sobieski in Zhuravno.

In September, King Jan III Sobieski in fact brought the Peace with the Ottomans even before the Battle of Zhuravno. The King gave a large monetary bribe to Ibrahim Pasha with King’s Commissars on September 10th, 1676. Before the Battle of Zhuravno, the King decided to sign the treaty. However, the battle in Voynyliv and Dovha radically changed all of the King’s plans.

The Battle of Zhuravno became a historical battle even though the King probably "bribed" at least Ibrahim Pasha and after Voynyliv battle, he neutralized the Tatars khan Selim Girey.

The Polish government suspected that the King Jan III Sobieski already made peace with the Ottomans and rejected his request for more money for the army because the King would have used the money for his own purposes [427].

The Treaty of Zhuravno escalated the war between Sweden and Muscovy because the Commonwealth had the Treaty of Zhuravno with the Ottomans, and Jan III Sobieski had an agreement (1676) with Sweden and according to the French policy, these three powers must "block" Muscovy.

The Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia would be with the Muscovy state when the war started against the Ottomans [428].

After the conquest of Moldavia and Wallachia the Ottomans wanted to destroy and enslave the Ukrainians [429]. Sweden saw the Ukrainian state as a strategic place in the wars against Muscovy and the Commonwealth. The occupation of the Ukraine would connect Sweden to the Ottomans and Crimea Khanate with whom Sweden kept alliance with in the 17th century.

The Ottoman Porte was in the period of economic crisis and desperately needed new territories and wars. That is why the Ottomans started looking to Hungary, the Commonwealth, and the Right-Bank Ukraine. The political power of the Vizier (Keprulu) in the Ottoman Porte supported the militarization of the state. The Crimea Khanate, Moldavia, Wallachia, and the province of Podillia had to play the role of the strategic place against the Commonwealth, the Cossack’s Ukraine, and Muscovy. The Commonwealth was weak in the second half of the XVII century and after 1672 (The Treaty of Buchach) even became a vassal to the Ottomans by paying yearly taxes until 1676 (The Treaty of Zhuravno).

From the perspective of the Russian historiography, the Commonwealth paid taxes to the Ottomans using the Ukrainian land and Ukrainian peasants. The Commonwealth usually used the Ukrainian Cossacks as the undefeated military army in their own aggressive plans in the Black Sea region.

The unstable situation of the "Ukrainian Cossack’s State, " was very significant in Europe. France, during the reign of Louis XIV, tried to block Muscovy, using the Commonwealth, Sweden and the Ottomans. In the view of the French military there were three active armies: the Ottoman, Sweden, and the Ukrainian Cossacks in the second half of the 17th century. This "block policy" against Muscovy was even accepted by England and the Netherlands because they wanted to keep Muscovy out of trade interests in the Baltic Sea area and France was an ally to the Ottomans and Sweden. Only the Ukrainian Cossacks were neither allied with the Commonwealth nor the Ottomans. The question was "with whom would the Ukrainian Cossacks be allied?"

The Commonwealth signed an eternal truce (The Truce of Zboriv, 1649) with Crimea Khanate [430] against the Ukraine. After the Truce of Pereyaslav (1654) with Muscovy, Ukraine became the "natural" enemy of the Commonwealth, the Crimea Khanate, Sweden, and the Ottomans because of the alliance with Muscovy. In this political situation, the Ukrainian Hetman Petro Doroshenko, in 1669, became a vassal of the Ottomans, using the tactic of balancing policy between the Commonwealth and Muscovy. The position of Hetman Petro Doroshenko supported the Ottomans in the Black Sea, the province of Podillia and the Moldavia region, moreover the Ottomans started a new war against the Commonwealth from 1672 to 1676 using Ukrainian Cossack’s armies too [431].

The Commonwealth signed the agreements with Muscovy in 1670 and 1672 to put diplomatic pressure onto the Ottomans. Now, the Right-Bank Ukraine again became the "central question" in East Europe. The Right-Bank Ukraine under the Hetman Petro Doroshenko became a keystone question for at least six states (the Commonwealth, the Ottomans, the Crimea Khanate, Muscovy, Sweden, and France). The Truce of Buchach in the October 22nd 1672, signed by the Commonwealth and the Ottomans, formally gave the Ottomans the province of Podilia and the Right-Bank Ukraine territories, as well as yearly taxes of twenty-two thousand "chervinciv" (Polish currency).

The Ukrainian Cossack’s Council of Pereyaslav, March 17th, 1673, appointed the Left-Bank Ukraine Hetman, Ivan Samoylovych, (pro Muscovy hetman) as the Hetman of all Ukraine. The Muscovy state officially claimed the cities of Kiev and Smolensk as well as the Right-Bank Ukraine in 1674, as the territories which were not returned to the Commonwealth, because the Commonwealth already lost these territories to the Ottomans by the Treaty of Buchach in 1672 [432].

The Ottomans also had agreements with England and France in 1673 and 1675. The Ottomans agreed to give the allies more trade freedom in the Ottoman Porte. The Swedish King Carl XI, as an ally with France and the Ottomans, occupied the province of Pomerania in the Commonwealth. The French diplomacy tried to organize the military block of the Ottomans, the Commonwealth, Sweden, and the Crimea Khanate against Muscovy using the Ukraine territory [433].

In 1675, the Ottomans lost against the Commonwealth King Jan III Sobieski, in the provinces of Galicia and Podillia, and Tatar Khan lost against the Zaporozhian Cossacks near Sevash (the portion of the Black Sea near Crimea Peninsula). The Muscovy army of Prince Romodanovsky occupied the fortress of Kopsun’ in the Right-Bank Ukraine. Under these circumstances, the Ottoman’s vassal, Hetman Petro Doroshenko, accepted political exile in Muscovy in September 9, 1676, during the reign of the Tsar Feodor III of Muscovy (1676-1682).

The Commonwealth, while the formal vassal of the Ottomans, despite the military victories of 1673 at Hotyn (town in Ukraine now), started regular diplomatic meetings with the Ottomans. The Ottomans demanded the provinces of Podillia and Volyn’, and both the Left and Right bank of Ukraine and the Commonwealth must remain neutral in its foreign policy in that (Eastern) area.

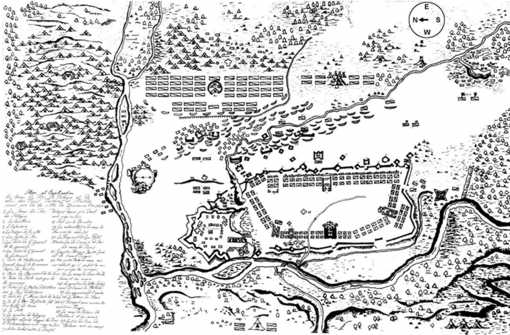

The battle of Zhuravno september 25 – october 14, 1676 Made by Jan Wimmer in: Wojsko Polskie w Drugej Polowie XVII Wieku, Warsaw, 1965 Based on Joannes Roode originally published in Leipzig, Holy Roman Empire, 1774

The signing of the treaty of Zhuravno in October 17, 1676 by king Jan III Sobieski of the commonwealth and Ibrahim Shaytan pasha of the Ottoman empire, commander of the ottoman forces in the battle of Zhuravno

Image from early 20th century postcard published by a Teutonic trading company in Zhuravno.

Oil Painting by January Suchodolski, Galicia, Austria, 1858. Destroyed in 1947 in the town of Zhuravno when the Roman Catholic Church was set on fire by the Soviet KGB

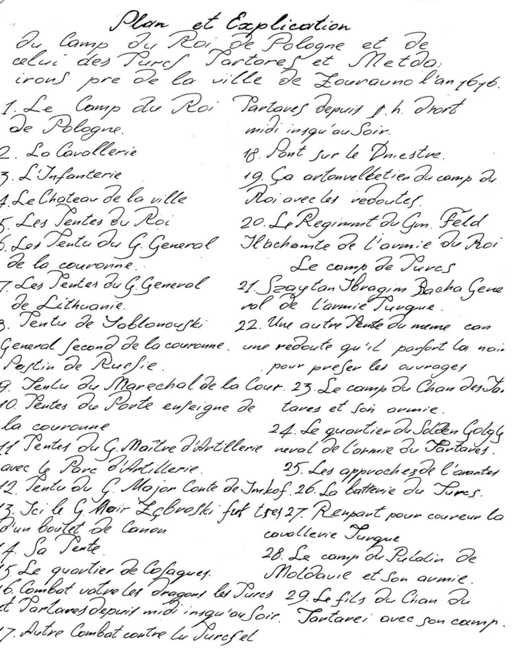

Zorawno Plan et Explication du Camp du Roi de Pologne et de celui des Turcs, Tartares et Monldaviens pre de la ville de Zurawno l’an 1676.

In the left underneath corner are 29 descriptions in the French language.

Transfer of the original Copper Relief, by Joannes Roode 38 cm × 25.5 cm. Sign.: the above map was created by J.D. Phillip geb Sysang sc. As a copy of Copper Relief, and was published in Historie de Stanislas Jablonowski, Castellan de Cracovie… par Msr. De Jonsac. A Leipzig, Holy Roman Empire, 1774. T. II page 46.

These 29 descriptions of the Battle near Zhuravno which took place in the fall of 1676 were written in the French language. They are a description of the map above

The monument dedicated to the Battle of Zhuravno 1676, constructed in 1876. This image is from a 19th century postcard, published by businessman H. Kronstein, in Zhuravno, Austro-Hungarian Empire

In the spring of 1676 the Ottoman army, led by Ibrahim Pasha of Damask and after his death, another Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha invented the provinces of Podillia and Galicia. In 1676, the Muscovy Tsar, Alexey Romanov, passed away and Muscovy lacked finances and troops so were not prepared for an aggressive war. The Crimea Khanate was in a war with Zaporozhian Cossacks of the southern Ukraine. The Right-Bank Ukraine, Hetman Petro Doroshenko, exiled himself to Muscovy from the Ottoman’s. This is why the Ottomans and the Commonwealth signed the Truce of Zhuravno on October 17th, 1676, which removed the Commonwealth from the Ottoman’s vassal’s position.

The Ottomans intended to press the Commonwealth to join their armies against Muscovy in the Ukraine. Muscovy did not agree with the Truce of Zhuravno and had the armies in the Right and Left Bank Ukraine. The Commonwealth blamed Muscovy because Muscovy did not help them against the Ottomans in 1676 and Muscovy only occupied the Right-Bank Ukraine without any agreement with the Commonwealth. At the same time, King Jan III Sobieski, told the Muscovy ambassador in Warsaw that the Treaty of Zhuravno was signed because the Commonwealth did not have military resources to continue the war [434].

It was feared that if the Ottomans occupied both banks of the Ukraine, the next would be the occupation of the Commonwealth. Jan Sobieski, the king of Poland and Lithuania, did not really want war against Muscovy. Furthermore, the diet of the Commonwealth in 1677 rejected the Treaty of Zhuravno.

However, the Truce of Zhuravno brought peace with the Commonwealth and Sweden which had been against Muscovy in 1676. It was totally according to the French plan to build a strong "block "of the states against Muscovy, England and the Netherlands; and maintain the coalition of the Ottomans, the Crimea Khanate, the Commonwealth, Sweden, and Hungary against England and the Netherlands which would block also Muscovy and Austria.

The Muscovy government created a special army commanded by prince Vasiliy Golicin to add to Prince Romodanovsky’s army in the Ukraine. Finally, in the year of the 1676, the Ottomans openly proclaimed war against Muscovy in the Right-Bank Ukraine.

The French diplomat, Marquise du Betune (the brother of the Polish Queen), tried to convince King Jan III Sobieski, to start war against Muscovy to regain the cities of Kiev and Smolensk and revise the Treaty of Zhuravno, King also was committed to helping Sweden against Muscovy as well.

During the time of the Treaty of Zhuravno, we can see a strong tendency of Moldavia and Wallachia to gain protection from Muscovy as the main protector of the Orthodoxy. However, the Ottomans reduced the payment of taxes required from Moldavia and Wallachia to ten years and brought them back under the Ottoman’s protection.

In 1677, the Ottomans lost the war against Muscovy in the Right-Bank Ukraine. The Ottomans Sultan arrested the military commander of the Turks, Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha, and expelled the Crimea Khanate khan Selim Girey from his throne and sending him to prison to the Greeks island of Rodos. In 1678, the Ottomans lost the war for Chyhyryn. The Truce was signed at Bakhchesaray on January 3rd, 1681. And finally in 1682, all Ukraine was divided by the Ottomans and Muscovy except with autonomy to the Zaporozian Cossacks, who gained complete autonomy from all European powers as well as the Ottomans. Muscovy now tried negotiating an agreement with the Commonwealth and Austria against the Ottomans. The Ottomans appointed the former Moldavian Hosbodar G. Duka to be a governor of the Right-Bank Ukraine. The Province of Podillia was included to the jurisdiction of the Ottoman’s Pasha (general governor) in Kamyanets-Podilsky. Even the 1683 Vienna victory did not bring back Kamyanec’-Podil’sky to the Commonwealth. Only the agreement between Muscovy and the Commonwealth on May 6th, 1686, stopped the Ottomans’ presence in the Right-Bank Ukraine and the Commonwealth lost the Left-Bank Ukraine to Muscovy and the cities of Smolensk and Kiev and all the lands of Zaporozhian Cossacks.

The Ukrainian historiography indicated the Treaty of Zhuravno and Hetman Petro Doroshenko’s exile as the final defeat of the Ukrainian Revolution (Februrary 1648-Septmember 1676) without success [435]. The Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) for the third time since 1667, partitioned the Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate. However neither the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) nor the Treaty of Buchach (1672) established political power of any monarch rulers because of the independent policy of the Hetman of the Right-Bank Ukraine, Petro Doroshenko. However, the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) had practical results to the Right-Bank Ukraine. The eight paragraphs of this Treaty regulated territorial boundaries between the Ottomans and the Commonwealth which were across the Right-Bank Ukraine. In the final Treaty of Constantinople (1678, which was the ratification of the Ottoman’s Treaty of Zhuravno, 1676), the Cossack’s Hetman was excluded from power in the Right-Bank Ukraine as had been under the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676). After the Treaty of Zhuravno and up to 1699 the Carlovitz Congress the Ottomans had internationally recognized right to posses the city of Kiev and the province of Podillia. The partition of the Right-Bank Ukraine in 1676 led to political-economic recession in the last quarter of the 17th century and had significant impact on European history in the next 18th century.

Under the Treaty of Zhuravno the Right-Bank Ukraine was not anymore subject to international law. This Treaty stopped the Commonwealth-Ottoman’s war, but did not relieve the conflict in the Right-Bank Ukraine. Now, Muscovy claimed the Right-Bank Ukraine "Russian" territory based on the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654) and Andrusovo (1667). The Commonwealth-Muscovy conflict exacerbated; the Ottomans started war against Muscovy and the Left-Bank Ukraine (Hetman Ivan Samoylovych) in the territory of the Right-Bank Ukraine (1677 and 1678). Neither Muscovy nor the Left-Bank Ukraine nor the Ottomans looked favorably on the Treaty of Zhuravno. The Commonwealth and Muscovy were both helpless without more money and soldiers to continue the war. The Commonwealth did agree on the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) and in 1678, signed new the Commonwealth-Muscovy Treaty that was the same agreements they had signed in 1667 [436].

In summary, we can conclude that the Treaty of Zhuravno (1676) and its ratification in 1678 as the Treaty of Constantinople had a significant impact on the Ukrainian Revolution (1648-1676) and the Ukrainian State (Hetmanate) which provided their poly-vassal foreign policy. It can be seen that neither the items of the Andrusovo Truce (1667), nor the Buchach Peace Treaty (1672), nor the Zhuravno Treaty (1676), nor the Bahchesaray Peace Treaty (1681), nor the Eternal Peace Treaty (1686), nor the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) can be viewed as a complete position of the hetman governments on the Left and Right Bank Ukraine. The Zhuravno Treaty did not establish the conclusive rule of one of the sites under the whole territory of the Cossack Ukraine. At the same time, it is recognized that the active role of the Ukrainian Cossacks in the Commonwealth and Muscovy armies succeeded in the important military campaigns against the Ottomans (in Vienna 1683 and Azov 1696) as well as in Zhuravno in the 1676 [437].

The Commonwealth, the Ottomans, Sweden, and Muscovy (since1654) were permanently in a state of war throughout 17th Century. The most harmful was the Commonwealth war against the Ottomans, Tatars and Moldavians in 1672-1676. Even thought the Commonwealth won the Battle near Zhuravno and the Ottomans called for peace, the Commonwealth lost the advantage of the victory because of lack of understanding of the Eastern European reality of the 17th century. However, because the main events took place in the territories of the Right and Left Bank Ukraine, it is significant to understand that in 17th Century, at least from 1648 to 1676, Ukraine was a dominant factor in the foreign policy of the Commonwealth, Muscovy, the Ottoman, and the Crimea Khanate as well as France, Sweden, Brandenburg, and Austria [438].

Even now Ukraine still is between the European Union, NATO and Russia, and still plays important role in the all European policy.

Примітки

406. Rendering Eastern European terms and place names in a work in English may cause a serious misunderstanding. The mixture of languages spoken in the area covered by this article include- Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and Turkish- one must also acknowledge political changes, which have occurred recently. All foreign terms are in general given in English (e.g. Shaytan and Zhuravno) with the exception of a few important historical terms adopted in English such as Hetman, (from the German Hauptmann and the Polish hetman: ’leader’. The title was also used for the supreme military commander both in Poland and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. At the end of the 16th century the commander of the Cossacks also became known as the hetman. From 1648 the hetman was the head of the Cossack Hetman state. In this capacity he had broad powers as the supreme commander of the Cossack army; the chief administrator and financial officer, presiding over the state’s highest administrative body, the General Officer Staff; the top legislator; and from the end of the 17th century, the supreme judge as well. The first hetman who was also head of the state was Bohdan Khmel’nytsky 1648-1657.) Hospodar was a title of the rulers of Moldavia and Wallachia were styled hospodars in Slavic writings from the 15th century to 1866. Hospodar was used in addition to the title voivod) and Pasha (who was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire political system, typically granted to governors, generals and dignitaries. Ibrahim Shaytan pasha was the Ottomans governor in the province of Podillia and military commander in the Ottoman army).Therefore, with regard to geographical places situated in Modern Ukraine, all Ukrainian forms have been preferred to Polish (thus: Zhuravno, not Zurawno or Zorawna, Buchach not Buczacz, Lviv not Lwow, Kamyanec’Podil’sky not Kamieniec Podolski, Podillia not Podole, Voinyliv not Wojnilow). The integrity of historical terms has also been preserved in the footnotes and the bibliography, which in text of the article will be the "Treaty of Zhuravno" not the "Treaty of Zurawno." In a few cases, English equivalents, such as Kiev, Dnieper River, are given instead of the local names. The Muscovy state in the article will be not called Russia, because the title the Russian empire became the official name of the Muscovy state after 1721.

The name of the Ukrainian Cossack state, the Hetman State or Hetmanate, existed from 1648 to 1782. It came into existence as a result of the Cossack-Polish War and the alliance of the registered Cossacks with the Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Sich and other segments of the Ukrainian populace. The territory of the state at the time of the hetman, Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1648-57), consisted of most of central Ukraine as well as part of Belarus. This Cossack state was the troublesome borderland in the 17th century. In 1663 the Hetman state in Right-Bank Ukraine came under Polish domination, while the Left Bank Ukraine came under Muscovite control in 1667.

"The Ruin" – is a period of civil war between the various Left- and Right-Bank hetmans, backed by their respective supporters, attempted to re-establish a unitary state. Despite these efforts, the partition of the Hetmanate was confirmed by the Muscovite- Polish Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) and the Eternal Peace of 1686. It was the period between the death of Hetman Bohdan Khmel’nytskyy (1657) and the end of the seventeenth century in the history of Ukraine, characterized by the disintegration of Ukrainian statehood and general decline. During the Ruin Ukraine became divided along the Dnieper River into Left-Bank Ukraine and Right-Bank Ukraine, and the two halves became hostile to each other. Ukrainianleaders during the period were largely opportunists and men of little vision who could not muster broad popular support for their policies. The hetmans who did their utmost to bring Ukraine out of decline were Ivan Vyhovsky, Petro Doroshenko, and Ivan Samoilovych. The main hetmans in the article are: Petro Doroshenko the hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine from 1665 to 1676. In January 1666 he was elected hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine. Doroshenko’s main aim was to restore the Hetman state on both banks of the Dnieper River. Petro Doroshenko was proclaimed hetman of all Ukraine on 8 June 1668 and abdicated, on 19 September 1676. Yurii Khmel’nytsky the hetman of Ukraine (1657, 1659-63) and hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine (1676-81, 1685). Khmel’nytsky was elected hetman of Ukraine, supported primarily by the pro-Muscovite Cossack families in 1657 and 1659-63 and as the Ottomans vassal in 1677-81 and 1685. Capitalizing on the anarchy that was developing in Ukraine and Khmel’nytsky’s inexperience and weakness, the Muscovite government forced Khmelnytsky to ratify the Pereyaslav Articles of 1659, which limited the sovereign rights of Ukraine and after the Treaty of Zhuravno the Right-Bank Ukraine under Yurii Khmelnytsky became a vassal of the Ottomans. Ivan Samoilovych, the Cossack leader who was elected hetman of Left-Bank Ukraine. He sought to unite Left-Bank Ukraine and Right-Bank Ukraine under his rule and fought against the Right-Bank hetman, Petro Doroshenko. On 17 March 1674 a council of 10 senior Cossack starshyna officers of Right-Bank Ukraine recognized him as their hetman, but he could not rule de facto until Doroshenko abdicated, on 19 September 1676. Samoilovych opposed a Muscovite-Polish alliance, but he supported peaceful relations between Moscovy and the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans.

407. See primary sources in: Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, Ottoman-Polish Diplomatic Relations (15th- 18th Century) An Annotated Edition of ’Ahdnames and Other Documents. Brill, Leiden, Boston, Koln, 2000. Document 53 (15 October 1676) The Polish Document of the agreement of Zurawno, Document 53A (14 October 1676) Another version of the Polish document of the agreement of Zurawno, Document 54 (17 October 1676) The ottoman document of the agreement of Zurawno, Document 55 (4-13 April 1678) The ’adhname sent by Mehmed IV to King John III, Document 56 (14 October 1680) The Polish protocol of demarcation, Document 57 (15-24 October 1680) The Ottoman protocol of demarcation. pp. 515-580.; "Liber Memorabilium Ecclesiae parachialis rit. lat. Zuravnensis confectus 1835. Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoyi Academiyi Nauk Ukrainy im. Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopusiv. Fond YK-50 "Zurawno".; Dyariysz y Pakta Tureckie Zorawinskie. Bibl. Ossolineum we Wroclawiu mkf. Bibl. Narodowa. #3952. # renkopisu w bibl. Wroclawskej 122. Andr Chrisostomus Zalusky, T.I. Epistola XXXIV.s. 611-619 Eidem Nuntio Apostolico Idem 29 Decembris. Relatio qua in Castris sunt a Etaante e post Coronationem Sub Zurawno. Lviv Biblioteka Ridkisnoi knyhy. In: Jozef Ignacy Kraszewski, Adama Polanowskiego dworzanina Krola Jegomosci Jana III. Notatki (1698r.) Warsaw, 1986. In: The Memoirs of Jan Chryzostom z Goslawic Pasek. Translated with an Introduction and commentaries, by Maria A. J. Swiecicka. New York, Warsaw, 1978 In: Memoirs of The Polish Baroque, The Writings of Jan Chryzostom Pasek, A Squire of the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. Edited, translated, with an introduction and notes by Catherine S. Leach. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1976. Biblioteka Narodowa. Zorawinski Pakt. A Warszawa III 6639-Ark. 169-173 Traktaty Zurawinskie Dyaryusz y Pakta Tureckie Zurawinskie. Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoyi Academiyi Nauk Ukrainy im. Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopysiv. Fond 45 Dzieduszicki Op. 1Spr. 575 Ark. 1. (Partial Manuscript about Peace Treaty of the Commonwealth and the Ottomans after the Battles near Zhuravno from the 13 th of September to the 17th of October 1676. Explanation of this document is in: Volodymyr Yahnishchak, An Unkown Diary about Russia, Poland and Turkey in the 17th Century. KRAJ Historical Journal. Lviv: KRAJ, 2002.; Papiery Rozwadowskich. Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoyi Academiyi Nauk Ukrainy im. Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopusiv. Fond Papiery Osobiste Rodziny Polanowskich. A 69. Ark. 243, 245.; Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoi Academii Nauk Ukrainy im. Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopusiv. Fond. 6.Korduba M. YK-21 Samoil Velychko, Letopys’ sobytiy v Yuoozapadnoy Rossii, vol. 2 (Kiev, 1851) Litopus Samovydtsya (Editor Ya. I.Dzyra) K. 1971 Zrodla do poselstwa, Jana Gninskiego wojewody chelminskiego do Turcji w latach 1677-1678…, wyd. F. Pulaski, Warsaw. 1907. (Biblioteka Ordynacji Krasinskich, T. XX-XXII); Jan Sobieski (King of Poland), Listy do Marysienki, t. I-II opracowal Leszek, Kukulski. Warszawa, 1973 .; Akty otnosiashchiesia k istorii Yuzhnoy i Zapadnoy Rossii.-SPb. 1883. – T.12. – pages 751-752).

408. Natalia Yakovenko. Essays of History of Ukraine.From the Earliest Times until the End of the 18th Century, Kiev, 1997.

409. Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks. Cambridge History of Europe, Early Modern Europe, 1450-1709. Cambridge University Press. 2008.; Valerie A. Kivelson, Autocracy in the Provinces: The Muscovite Gentry and Politial Culture in the Seventeenth Century. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996. Revor Ashton, ed., Crisis in Europe, 1560-1. Rhoads Murphy, Ottoman Warfare, 1500-1800 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999); Simon Dixon, The Modernization of Russia, 1676- 1825 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999); Serhii Plokhy. The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine, Oxford University Press. 2001.

410. See: Dmytro Doroshenko, Het’man Petro Doroshenko: Ohliad ioho zhyttia i politychnoi diial’nosty. Edited by V. Omel’chanko. (New York, 1985).; Perdenia, J. Hetman Piotr Doroszenko a Polska. Cracow. 2001.

411. Paul Wittek, The Rise of the Ottoman Empire (London, 1938) On the struggle for domination over the eastern European steppes between the Otoomans, Russia (Muscovy), and Poland- Lithuania, see the study by William McNeill, Europe’s Steppe Frontier 1500-1800 (Chicago, 1964) On the East European policy of Louis XIV see: Jean Berenger "Lous XIV l’Empereur et "Europe de l’Est, " XVII, siecle. Revue puliee par la Societe d’Etude du XVII siecle 31 (1979): 173-94; Shaw, Stanford Jay, and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. 1997.

412. Akty otnosyiashchiesia k istorii Yuzhnoi I Zapadnoi Rossii, vol. 12 (St. Petersburg, 1882), pp. 755-59.

413. The commissioners were Prince Konstanty Wisniowecki, Jerzy Wielhorski, Tomasz Karozewski, Franciszek Kobytecki, Stanistaw Dabrowski, and Jan Telefus. The seventh commissioner Jan Karwowski had been preciously sent to the Moldavian hospodar and thus was present in the Ottoman camp. One of these men wrote diary about the Battle near Zhuravno and Voinyliv and the Treaty of Zhuravno in 1676.This document is in: Traktaty Zurawinskie Dyaryusz y Pakta Tureckie Zurawinskie. Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoyi Academiyi Nauk Ukrainy im.Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopysiv. Fond 45 Dzieduszicki Op. 1Spr. 575 Ark. 1.; and "Liber Memorabilium Ecclesiae parachialis rit. lat. Zuravnensis confectus 1835. Naukova Biblioteka Nacionalnoyi Academiyi Nauk Ukrainy im. Vasylya Stefanyka y Lvovi, Viddil Rukopusiv. Fond YK-50 "Zurawno". :(Partial Manuscript about the Peace Treaty of the Commonwealth and the Ottomans after the Battles near Zhuravno from the 13 th September- to the 7th of October 1676, .For the explanation of this documents see: Volodymyr Yahnishchak, An Unknown Diary about Russia, Poland and Turkey in the 17th Century. KRAJ Historical Journal. Lviv: KRAJ, 2002.

414. See: Aleksander Czolowski. Wojna Polsko-turecka 1675 r. Lwow. 1894. Fr. Kluczycki, Zorawinska R. 1676 Pod 200-Letnia Rocznice Krakow. 1876. Janusz Wolinski, Z dziejow wojen polsko-tureckich. Zorawno. Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Naradowej. Warsaw. 1983. Janusz Wolinski, Z dziejow wojny i polityki w dobie Jana Sobieskiego. Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Naradowej. Warsaw. 1960 Janusz Wolinski, Zorawno, "Przeglad Historyczno-Wojskowy, " R.t.II zasz l, Warsaw, 1930., Materialy do rokowan polsko-tureckich z. 1676 PH, t XXIX. 1930-1931 (Archiwum Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Warszawie. Teki Janusza Wolinskiego).; Krol Jan III a sprawa Ukrainy 1674-1675. Warsaw. Sprawy Narodowosciowe. R.8 #4 1934. (Bibloteka Spraw Narodowosciowych "# 2.19.").; Janusz Wolinski. Materialy do dziejow wojny polsko-tureckiej 1672-1676.In:Studia i materialy do historii wojskowosci.Tom XVI.Chapter II.Warsaw.1970., p.240-253.; Tadeusz Korzon, Dzieje wojen I wojskowosci w Polsce, Krakow, 1912Tadeusz Korzon, Dola I niedola Jana Sobieskiego. T. III Krakow, 1898.K. Gorski "Jan III pod Zorawnem, " "Biblioteka Warszawka, " 1896, III s.378. Jan Wimmer, Wojsko polskie w drugej polowie XVII wieku . Warsaw, 1965. (Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej).; Zbigniew Wojcik, Rzeczpospolita wobec Turcji i Rosji 1674-1689. Studium z dziejow polskej polityki zagranicznej. Wroclaw. 1976.

415. The best explanation of temessuk one can find in Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, "Ottoman-Polish Diplomatic Relations…" and Viorel Panatie, " On Ottoman-Polish Diplomatic Relations", Asian Studies. International Journal for Asian Studies (Studia Asiatica. International Journal for Asian Studies), issue: II / 2001, pages: 189-197, on "www.ceeol.com". To sum up, the temessuk-type document can be described as a highly flexible instrument composed by Ottoman negotiators together with the Christian envoys, often on the letter’s initiative, and therefore highly influenced by European forms and terminology. Sometimes a temessuk consists merely of a literal translation of a Latin document prepared by Christian envoys, supplemented with an Islamic invocation, narration, and the seal pence or signature of the Ottoman official. Among the Ottoman plenipotentiaries who issued the "Polish" temessuk in Zhuravno was Ibrahim Shaytan Pasha. This document was issued in Ottoman military camp at Zhuravno. The Ottoman temesuk is ironically dated the second decade of Shaban (19-28 October) instead of the first decade. The commissioner’s relation on the negotiations and their instruction is published in : Janusz Wolinski, "Materialy do rokowan polsko-tureckich r 1676", Przeglad Historyczny 29 (1930- 1931):382-413; see also: Zbigniew Wojcik, Rzeczpospolita wobec Turcji:Rosji 1674-1679 (Wroctaw, 1976), pp. 67-75.

416. See Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, Ottoman-Polish. the term ’ahdname a Persian-Ottoman term consisting of two words: ’ahd (oath, promise, pact) and name (Persian "letter"). The term stressed the fact that a written oath or promise to keep the peace was inserted into an imperial letter.

417. Jozef Ignacy Kraszewski, Adama Polanowskiego dworzanina Krola Jegomosci Jana III. Notatki. (1698r) Warsaw, 1986.

418. Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, Ottoman Podilja: The Eyalet of Kam"janec 1672-1699" Harvard Ukrainian Studies (1992):87-101. The Ottoman Survey Register of Podolia (ca. 1681) Cambridge, Mass., 1999 (in press) Podole pod panowaniem tureckim. Ejalet Kamieniecki 1672-1699. Warsaw, 1994.

419. See Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, Ottoman-Polish. Document 55 P 528-544, This document published in Pulaski, Zrodla do Poselstwa Jana Gninskiego, pp. 311-23. English translation of the articles was published in Demetrius Cantemir, The History of the Growth and Decay of the Ottoman Empire (London, 1734-1735), pp.284-86.

420. Nolan, Cathal J., Wars of the age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715 ABC-CLIO. 2008.

421. "The Ruin" – is a historical term used by European historiography to refer to the period between the death of Hetman Bohdan Khmel’nytskyy (1657) and the end of the seventeenth century. Some historians (eg, Mykola Kostomarov) correlate it with the tenures of three Moscow-backed hetmans (Ivan Briukhovetsky, Demian Mnohohrishny, and Ivan Samoilovych) and limit it chronologically to 1663-87 and territorially to Left-Bank Ukraine. Other historians consider the Ruin to apply to both Left- and Right-Bank Ukraine from the death of Bohdan Khmelnytsky to the rise of Ivan Mazepa (1657-1687). See: Taras Chuhlib. The Ruin of the Right- Bank Ukraine // The History of Ukraine: new – K., 1995. -T.1. Ohloblyn O.P.Do istorii Ruiny // Zapysky istoryko-filologichnogo viddilu VUAN. Kn.XVI. – K., 1928.;Yakovleva T. The Ruin of the Hatmanate:From the Council of Pereyaslav-2 to the Andrusovo Treaty (1659- 1667) / Transl. by L. Bilyk. – K. 2003.; Kostomarov N.I.Sobranie sochinenii.Istoricheskie monografii i issledovania .- Kn.6. – T.XV: and: Ruina Hetmanstva Bryuhoveckoho, Mnohohreshnoho i Samoilovicha. Sankt Petersburg, 1905. Yakovleva T. Het’manshchyna u druhy polovyni 50-h rokiv XVII stollttya. Prychyny i pochatok Ruiny. – K., 1998.

422. N.A. Smitnov, Rossia I Turcia v XVI-XVII ww., vol. 2 (Moscow, 1946), pp. 165-67

423. Samoil Velychko, Letopys’ sobytiy v yuoozapadnoy Rossii, vol. 2 (Kiev, 1851) pp.528-29

424. Krykun, M. Administrativno-territorial’noe ustrojstvo pravobereznoj Ukrainy x XV-XVIII vv. Granicy voevodstv v svete istochnikov. Kiev, 1992.

425. See Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, Ottoman-Polish. Document 56-57. pp.545-580.

426. The Russian historiography of the Treaty of Zhuravno is based on fundamental monograph of A.Popov, Russkoe posolstvo v Polshe v 1673-1677 gg. St. Petersburg, 1854, and main documents in this monograph are diplomatic missions’ letters, and reports made by Muscovy ambassador/resident Vasily Tiapkin in Warsaw during his diplomatic mission of 1673-1677; A.Popov. Russkoe Posolstvo. p. 244.

427. Tyapkin’s Letters from Warsaw on September 8th and 23rd, 1676. In: A. Popov, Russkoe… p. 220-221.

428. A. Popov. Russkoe Posolstvo." p. 196-197 Vlasova L.V.Vzglyady Dmitria Kantemira na razvitie moldavsko-osmanskix politico-pravovix otnosheny v XV- nachale XVIII v.//Social’no- economicheskaya I politicheskaya istoria Moldavii.-Kishinev, 1988. P. 110-111. Sovetov P.V. Proekty vstuplenia Dunaiskix knyiazhestv v poddanstvo Rossii I Rechi Pospolitoy v XVII- nachale XVIII v.//Rossia, Pol’sha i Prichornomorie v XV-nachale XVIII vv.- Moscow, 1979.

429. Tyapkin’s Letters from Warsaw on September 8th and 23rd, 1676. In: A. Popov, Russkoe. p. 220-221.

430. A. Popov. Russkoe Posolstvo." p. 196-197 Vlasova L.V.Vzglyady Dmitria Kantemira na razvitie moldavsko-osmanskix politico-pravovix otnosheny v XV- nachale XVIII v. // Social’no- economicheskaya I politicheskaya istoria Moldavii.-Kishinev, 1988. P. 110-111. Sovetov P.V. Proekty vstuplenia Dunaiskix knyiazhestv v poddanstvo Rossii I Rechi Pospolitoy v XVII- nachale XVIII v. // Rossia, Pol’sha i Prichornomorie v XV-nachale XVIII vv. – Moscow, 1979.

431. N.A. Smirnov, Borba Russkogo i Ukrainskogo narodov protiv agressii Sultanskoy Turcii v XVII veke. Journal, "Vosprosy Istorii, " Moscow, 1954 pp. 91-105.; N.A. Smirnov, Rossia i Turcia v XVI-XVII vv. T. II. Moscow, 1946.; V.D. Smirnov, Krimskoe Khanstvo pod predvoditelstvom Ottomanskoy Porty do nachala XVIII veka. St. Petersburg, 1887, A Course in Russian History-The Seventeenth Century. V. O. Kliuchevsky – author, Natalie Duddington – transltr. Publisher: M.E. Sharpe. Armonk, NY. 1994; Galaktionov I.V. Ukraina v diplomaticheskih planah Rossii, Pol’shi, Kryma i Turcii v konce 60-h gg. XVII v. // Slavyanskiy sbornik. – Vyp. 3.-Saratov, 1985; The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire. 1650-1831, John P. Ledonne; Oxford University Press, 2004.

432. Pamiatniki, uzdannye vremennoyu komissiey dlia razbora drevnih aktov, " Kiev, 1845 otd III, page 103-104, 107-115.

433. N.N. Bantysh-Kamenskiy. Istochniki Malorossiiskoy istorii. Ch. I Moscow, 1858, page 208; Jan Wimmer. Wojsko polskie w drugej polowie XVII wieku. Warsaw. Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej. 1965. p. 126-127, 163-164;

434. A. Popov. Russkoe posolstvo v Polshe v 1673-1677 gg. St. Petersburg, 1854, page 109.

435. "Voprosy Istorii". p. 99.

436. A. Popov. p. 244.

437. See the Ukrainian historiography of the period of the Treaty of Zhuravno 1676: Hrushevsky M. Spoluchennya Ukrainy z Moskovshchynoyu v novishiy literaturi. Krytychni zamitky // Ukraina.- K., 1917. – Kn. 3/4.; Smoly V.A., Stepankov V.S. Pravoberezhna Ukraina u druhiy polovyni XVII- XVIII st.: problema derzhavotvorennya. – K., 1993. And the same authors: "Ukrains’ka derzhavna ideya" – K., 1997; Dyplomatychna borot’ba za zberezhennya Ukrains’koi derzhavy. Peretvorennya Ukrainy na obekt mizhnarodnyh vidnosyn (1657 – XVIII st.) // Narysy istorii dyplomatii Ukrainy. – K., 2001; Ukrains’ka nacional’na revolyuciya XVII st. (1648-1676 rr.). – K., 1999; Apanovych O.M. Zaporiz’ka Sich u borot’bi proty turec’ko-tatars’koi ahresii u 50- 70-h rokah XVII st. – K., 1961; Mel’nyk L.H. Livoberezhna Hetmanshchyna period stabilizacii (1669 – 1709 rr.) – K., 1995.; Chuhlib T.V. Hetmany i monarchy: Ukrainska derzhava v mizhnarodnyh vidnosynah 1648-1714 rr. – K., New York, In-t istorii Ukrainy NAN Ukrainy. Hetmany Pravoberezhnoi Ukrainy v istorii Central’no-Shidnoi Europe (1663- 1713). – K.;Ukrainsky hetmanat u protystoyanni derzhav Europy z Osmanskoyu imperieyu (1667- 1699rr.): mizhnarodne stanovyshche, zovnishnya polityka, zmina syuzereniv: Dys, .d-ra ist. Nauk # 07.00.02 // T. V. Chuhlib. – K.: In-t istorii Ykrainy NAN Ukrainy, 2008. – 495 p. Het’many Pravoberezhnoi Ukrainy v istorii Central’no-Shidnoi Europe (1663-1713). – K.: Vyd. dim «Kyevo- Mohylyans’ka Akad.», 2004; Kozaky i yanychary. Ukraina u khrystyyans’ko-musul’mans’kyh viynah 1500-1700 rr. – K., 2010; Osoblyvosti zovnishn’oi polityky I. Samoilovycha ta problema mizhnarodnoho stanovyshcha Ukrains’koho hetmanatu v 1672-1686 rr. // Ukrains’ky istorychny zhurnal. – Kiev "Diez- produkt", 2005. – N°2. – p. 48-67; Ukraina i Pol’shcha pidchas pravlinnya korolya Yana III Sobes’koho: poshuky vtrachenoho myru // Ukrains’ky istorychny zhurnal. – Kiev, "Naukova dumka", 2002. – N°1. p. 38-52; Mizhderzhavni vidnosyny u Europi na zlami Seredn’ovichchya i Rann’omodernoho chasu: problema syuzerenno-vasal’nyh stosunkiv // Ukraina v Central’no-Shidniy Europi (z naydavnishyh chasiv do kincya XVIII st.) – Kiev: Instytut istorii Ukrainy NAN Ukrainy. 2002. – N°2; Yakovliv A. Ukrainsko-Moscowski dohovory v XVII-XVIII vv. Warsaw, 1934.

438. Olexandr Hurzhuy, Taras Chuhlib. Hetmanska Ukraina. Kiev, 1997.

Опубліковано: Гетьман Петро Дорошенко та його доба в Україні. – Ніжин: НДУ ім. М. Гоголя, 2015 р., с. 200 – 222.